Life is structured in a manner that is arguably linear. An individual aims to progress from point A to point B, giving little to no thought of the space that exists in between. In most cases, the progression is evident, clear, and concrete. In others, the door is one that revolves; a continuous orbit; a ceaseless journey; a liminal space. As society has been formed, straight is the default. It is the immediate assumption, creating a universal understanding that each individual belongs, and those who don’t are caught in a space of their own either by choice or circumstance; or both.

A Room of One’s Own, as Woolf pitches, is a space where one exists in total isolation from the greater part of the world. While it is lonely, it may be safe. Where safety is provided, it may be a haven. Though isolation has never proven to aid the ills of loneliness. Although we should also consider how we are deprived of the luxuries enjoyed by others. The closet is enjoyed by those who are hidden, shielded from the prying and judging eyes of others. Though while the door can be opened, it is always a free-fall if one dares to step out. And while there is no lock, there exists a feeling that the door should remain untouched - the hinges kept still.

The chronic nature of coming out creates a liminal space. It is understood that coming out is never a one-time, exceptional instance that immediately impedes any further need to affirm one’s identity. Instead, it is a continuous series of conversations and each one brings about a different kind of response: good, bad or indifferent. Although our identity is never measured by the responses of others, we can’t help but seek validation in what they have to say. The space between the closet and ‘outside’ blurs the lines between what being ‘out’ is. Albeit each story is a tale distinct from the next but the feeling is universal.

However the closet is not an independent infrastructure: it forms part of a room. The room which is filled with the staples of our identity - that of which we put on display. The walls are hued, photos framed, books shelved and beds made. This room is still a haven - it provides privacy, independence and identity. In the moments where loneliness makes its presence known, we unlock the door. We invite people in; slowly and calculatedly, or all at once. Their eyes glaze over the space, questions being formed in their minds. There is a certain kind of vulnerability that comes with this act that is almost always unspoken.

Much can be said about ‘coming out.’ The term itself is interesting – to come out is to progress forward or depart from something. It is an action that should be voluntary, made with the independence of one's will at the time that they please. However, it is not as linear as making it from point A to point B. What lies beyond is inherently unknown – a testing of waters always ensues. One fails to really know whether the leap is one of faith or detriment. While we always prefer the former, the latter is an expected default.

Arguably, the act of ‘coming out’ may be viewed as redundant. Some may argue that the requirement to publicly articulate one’s identity is regressive - something practised to appease [straight] society. While this may hold some truth, the experience is also universal and has formed the bedrock of community and belonging. It is a manifestation of courage, bravery and perhaps even protest.

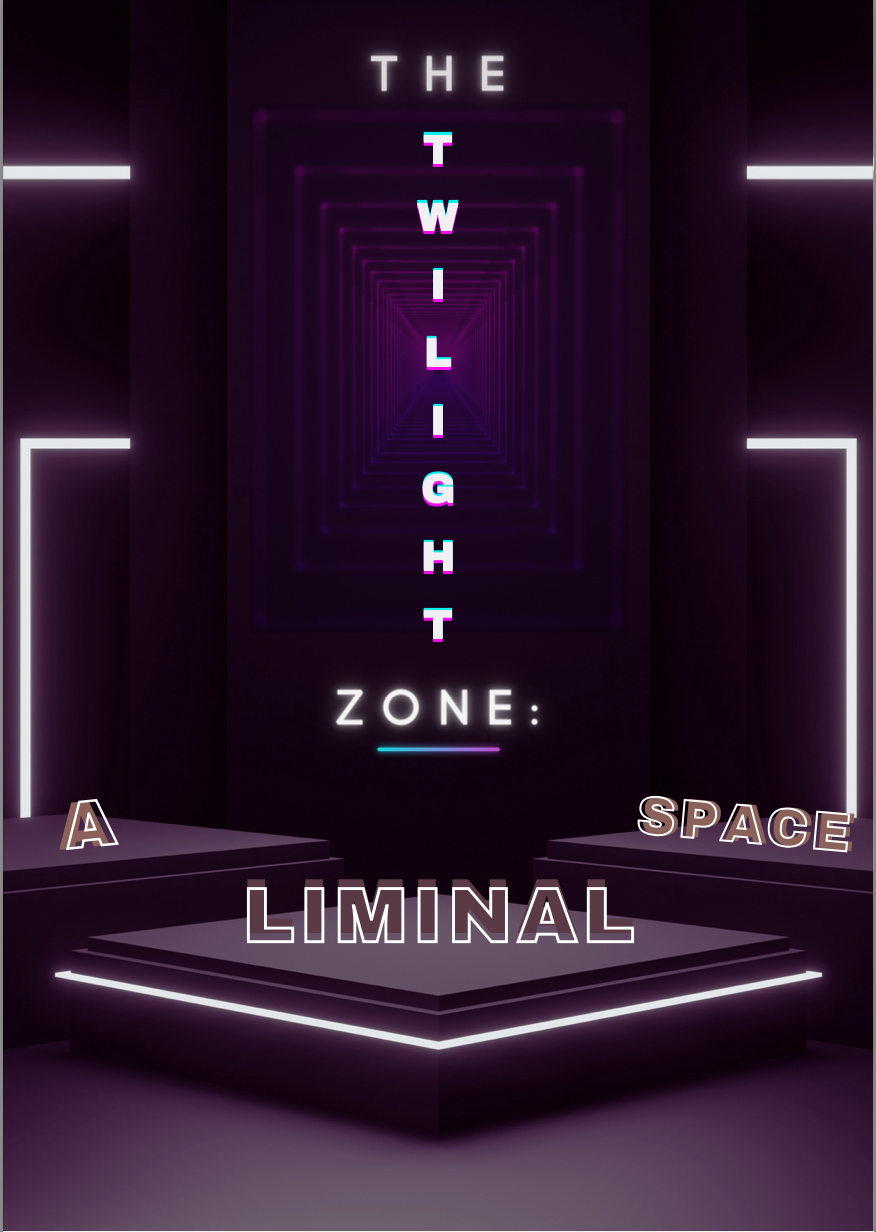

Queerness has always had to create a space of it’s own in a society that has attempted to conceal it otherwise. The existence of the closet is the consequence of an intolerant environment that denies individuals community, instead driving them into isolation. While each story reads differently as we all hold our own unique tale, the existence of the liminal space; the air between the closet, the room and beyond is often overlooked. Coming out remains a chronic process, and the closet becomes a sanctum sanctorum for many. The twilight zone almost holds a magnetic field, where one feels a pull between each point at each interaction. The foreign yet universal nature of this process binds us; forming connections and solidarities with unspoken words and untold stories.

Albeit while a room of one’s own bestows a comfort that is familiar, the window just above offers us a world we are deprived of. Further, while the liminal space tugs at both the hidden and the revealed, we are often constantly eclipsed. Belonging can feel like a distant concept out of one’s grasp and determined by the fate of coming out. The process illuminates drawbacks but it also highlights liberation. Indeed, the space in-between remains a constant home through it all.

Written by Angelene Concepcion and Ada Luong